網走からコツコツと、世界へ発信

流氷硝子館の歩みとこれから

流氷硝子館を立ち上げたいきさつ、これからの取り組みへの思いを皆様へより深くお伝えするために、

工房長の軍司昇と統括マネージャーの軍司知恵子がインタビュー形式で語りました。

(聴き手・フリーライター 細川美香、2021年3月収録)

ある本がガラスとの出会いのきっかけに

―昇さんがガラスに興味を持ったきっかけは?

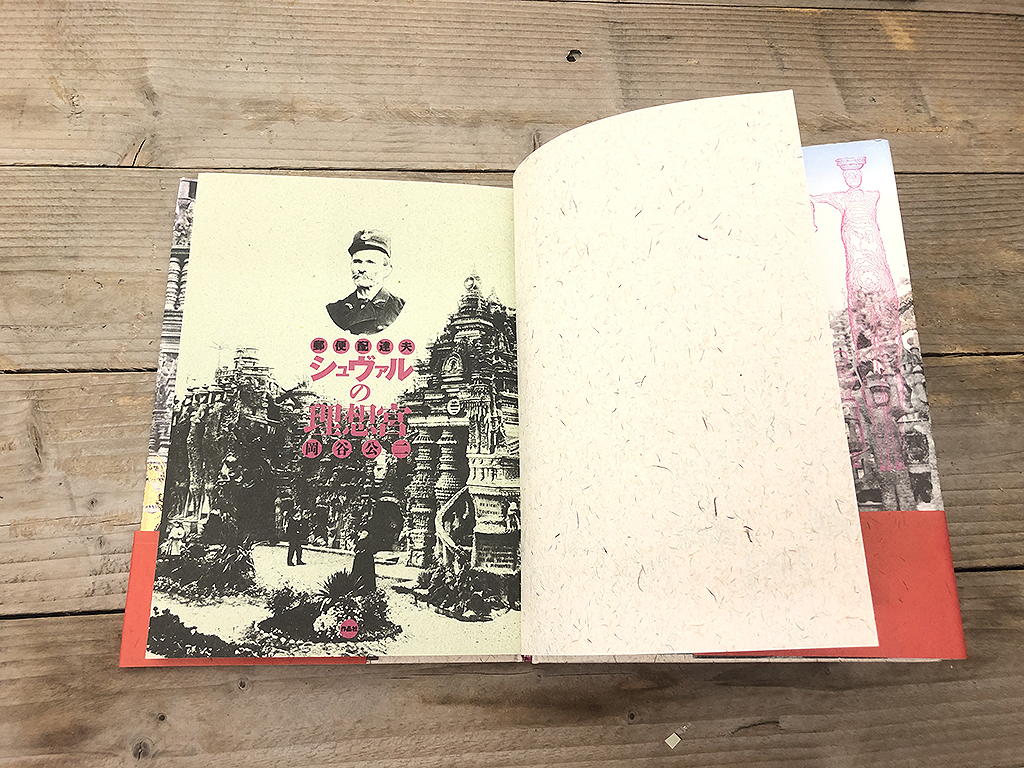

子どものころ、実家が玩具や子供服を売る小売店を経営していたので、将来は店を継ぐものと思っていました。ところが大学3年の時に父から、「店を辞めるからこれからの道は自分で考えろ」と言われたのです。それまで大学の授業にもあまり出ず就職活動もせず、アメフト部の活動に熱中していましたが、将来のことを考えざるを得なくなりました。 自分は何ができるだろう?と真剣に考えた時に、浮かんだのがものづくりの仕事です。子どものころから親戚に漁師と花卉農家がいたので、手を使ってする仕事には憧れがありました。クギを叩いてつぶしてナイフを作るなど原始的な遊びもしていましたね。 ちょうどその時、父から『シュヴァルの理想宮』という本を勧められました。

書籍「シュバルの理想宮」

父は大変な読書家で、たまに面白かった本や、私に合うと思った本を勧めてくれるんです。この本は、フランスの郵便配達員だったシュヴァルが、石につまずいたのをきっかけに石からインスピレーションを得て、それ以来配達途中に見つけた石を集め、配達物の中にある絵ハガキにある外国の建物をヒントに、30年以上をかけて宮殿を建てたという実話です。 この本の内容が衝撃的で、私にとっての転機になりました。「ものづくりを30何年続けていたら、その人にしか見えない面白い世界が見えるのでは」と。 それから本気でものづくりの仕事について調べ、陶芸の窯などに見学に行くようになりました。ある時、小樽のガラス工房に行ってみたところ、溶けた熱いガラスが生き物のように動き、固まるまでの間に職人が形を作っていく姿を見て、すっかり魅了されていました。

網走の風景

「これからどうしていこうか」と考えた時に、もう一つ頭に浮かんでいたのは大好きな地元·網走の風景です。ガラス作りの様子を見て、「網走でものづくりをしたい、工房を構えたい」という思いがガラスでなら叶うのではないかと思いました。そして氷や雪、湖水ときれいなガラス作品がリンクして見えたのです。 そうして、小樽の工房の方に相談したところ、ガラスの学校で幅広く技術を学ぶことを勧められ、大学は一旦休学して東京の学校に行くことに決めました。

知恵子 私は昇と大学で同級生だったのですが、「軍司くんは大学に来ないで何をやっているんだろう」と話題になっていて、ちょっと異色の存在になっていました。ガラスの学校に行くという選択も、今まで他で聞いたことがなかったので、驚きましたね。

大量に燃料を使うガラス製作に違和感

―そのガラスの専門学校で、大きな矛盾を感じたそうですね。

昇 最初の1年ほどは技術を覚えるのが楽しかったのですが、2年目からは次第に、綺麗なガラスを作るのに大量の燃料を使うことに矛盾を感じるようになって。

と言うのも、当時インターネットの動画で見た少女のスピーチに衝撃を受け、見える世界がすべて変わったんです。その動画は、1992年にブラジルのリオ・デ・ジャネイロで開催された「環境と開発に関する国連会議(環境サミット)」で、私と同じ年に生まれた12歳のセヴァン・スズキが世界の指導者たちを前に訴えたスピーチでした。

彼女は、オゾン層の破壊や野生動物の絶滅などの問題に対し、「どうやって直すのかわからないものを壊し続けるのは、もうやめてください」と訴えます。また、ブラジルで出会ったストリートチルドレンが「ぼくがお金持ちなら、家のないすべての子に食べ物と、着る物と、薬と、住む場所と、やさしさと愛情をあげるのに」と言うのに対し、「すべてを持っている私たちがこんなに欲深いのは、一体どうしてなんでしょう」と疑問を投げかけます。そして、子どもたちが将来生きていく世界を司る大人たちに対し、「あなたがたはいつも、私たちを『愛している』と言います。しかし、私は言わせてもらいたい。もしその言葉が本当なら、どうか、本当だということを、行動で示してください」という強い言葉でスピーチを締めくくりました。

私は以前から、網走で毎年見ていた流氷が減っていると感じていて、その原因である地球温暖化に少なからず問題意識を持っていました。そして、セヴァン・スズキのスピーチ動画を見ることで、その問題意識が確信に変わりました。その時から、仲間たちが楽しくガラスを作っている様子を見ていて苦しくなり、作品が作れなくなったんです。

1300℃でガラスを溶かす溶解炉

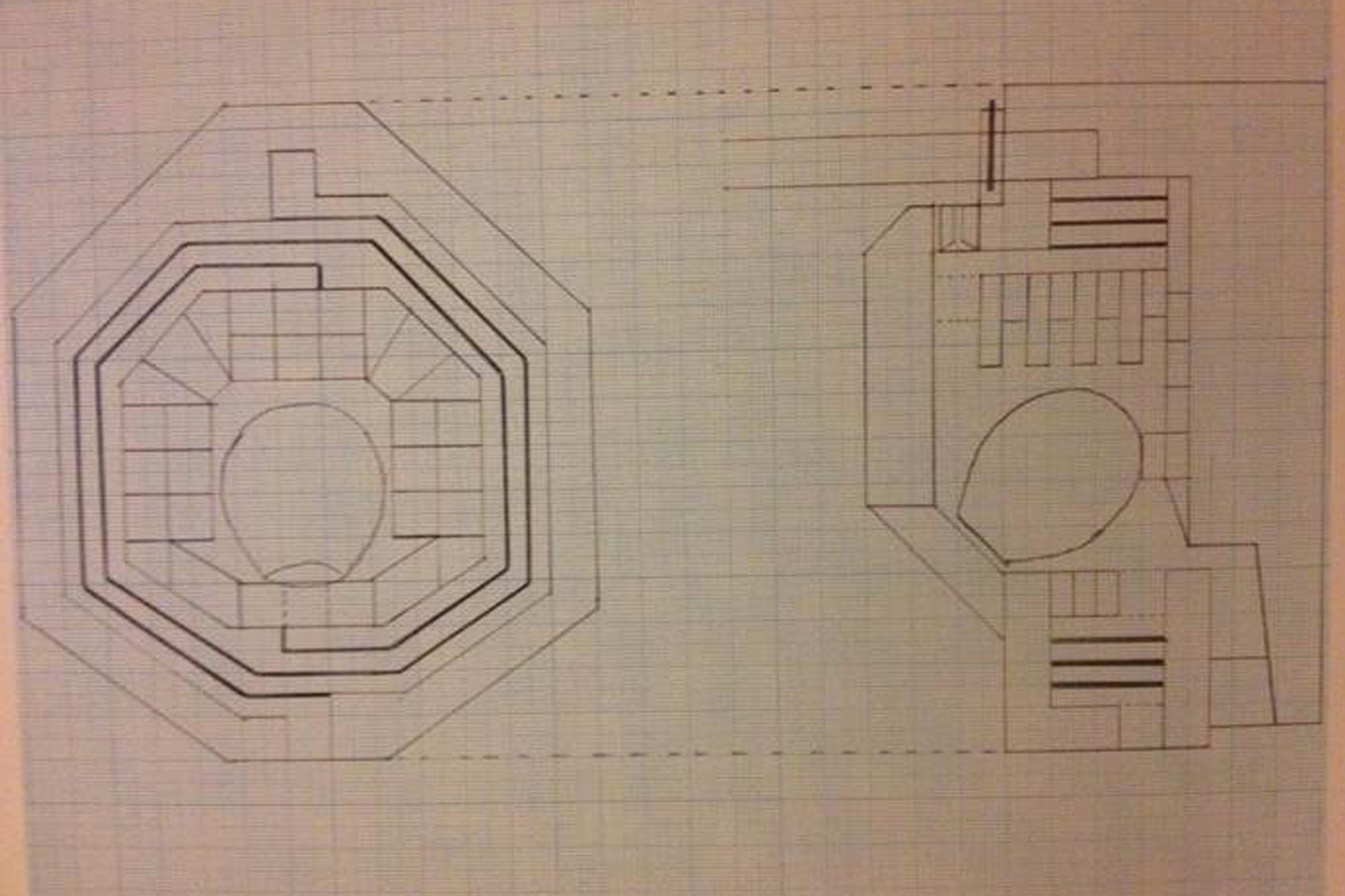

そこからは、矛盾を解消する道が始まりました。それが今の流氷硝子館の理念の原点ですね。まず、燃費を抑える窯の勉強を始めました。独学で工学書を読んで、こだわって窯を作っている工房に行って仕組みを教わったりして、紹介された本もまた読んで。 学校にも行かず工房を見て回って、灯油ファンヒーターを買って解体し、ガラス溶解用のバーナーを作ってみたりもしました。 専門学校では最後に卒業制作があるのですが、それをガラス作品ではなく熱効率の良い溶解炉の模型にして、パネルを貼ってプレゼンもしました。学校の先生はガラス作品を発表することを最後まですすめましたが、それを押し切って作った卒業制作です。 学校からは良い評価はもらえませんでしたが、見に来た作家さんは面白がってくれました。実際に工房を営んでいる人も同じ矛盾を抱えつつ、ガラスを作るためには仕方がないと思っていて、私の溶解炉の提案に関心を持ってくれたんです。 「やっぱり、これは必要なことだった」と確信し、これからもこの矛盾を解消していこうと決意しました。

卒業制作の溶解炉設計図

知恵子 昇は、小樽のガラス工房から専門学校に結びついた時もそうでしたが、行く先々でキーマンとなる人に出会っているんです。

昇 そうなんですよね。特に専門学校に通っていた2年間は不思議な期間でした。矛盾を感じながら先生に窯のことを聞いても、専門外なのでと教えてもらえない。でも一人の先生が、「窯の燃費にこだわっている工房があるので行ってみたら」と教えてくれたので、訪ねてみました。するとその工房の方が専門書を紹介してくれて、その後は書店に通い詰めて、流体力学や燃焼工学の本を読み漁っては、ガラスの窯に使えるかと考えていました。 そんな風に、求めている人や本にどんどん出会うことができ、目的も明確になっていきましたね。

地元で生産されるリサイクルガラスに出会う

昇 卒業後はさらに、原料の勉強もしようと思いました。就職したのは、沖縄の琉球ガラスの大きな工場です。琉球ガラスは、駐留米軍から排出されたコーラ瓶をリサイクルして使用したのがはじまりです。瓶のリサイクルガラスは細かい泡が残り、工業製品としては好まれないのですが、琉球ガラスではその泡をうまくデザインに生かしていて、勉強になりました。沖縄の人は、雪に馴染みがないのでその泡は潮騒など海のものとして表現していましたが、道産子の私にとっては、「これは雪でしょ、氷でしょ」と思っていました。自分で工房を開くときは、これを雪や氷として表現しようと、アイデアをストックしていましたね。

潮騒がモチーフの琉球ガラス

一方で、リサイクルガラスについてのリサーチを続けていました。窓ガラスや空き瓶を使っている工房はありますが、空き瓶は作っているメーカーによってガラスの組成が異なり、ラベル剥がしや、回収、選別が大変な労力になっていると聞いていましたし、融点が高いのでかなりの燃料を使います。しかし、使い終えた蛍光灯は均質で融点が低く、工芸用の吹きガラスの組成に近いことがわかりました。蛍光灯を処理する場所は全国各地にあるだろうと思い込み、父に頼んで探してもらったところ、さまざまな伝手を使いわかったのは、地元の網走の隣町、北見市留辺蘂町に、全国から廃蛍光灯が集まる野村興産㈱イトムカ鉱業所があるということ。そこで早速交渉し、原料の供給が受けられることになったので、1年後に沖縄の工場を退職して網走で流氷硝子館を開くことにしたんです。

野村興産株式会社イトムカ鉱業所

沖縄の工場で働いていた時に、ベトナムの直営工場に3カ月間、ガラス製作を教えに行く機会がありました。当時のベトナムは「これから頑張って行くぞ」と若者たちに勢いがありましたね。物がない中で手仕事をして生きているので手先も器用ですし、「給料を上げて良い暮らしがしたい」というハングリーさがあるのですぐに上達します。「日本人は器用」と教わって生きてきた私にはカルチャーショックでした。「ベトナムの人が技術を持って、こんなに綺麗なものを作っているのに、日本で同じようにものづくりをする必要があるのか?」と自問自答していたところ、地元で供給される原料で環境に優しいガラスが作れるというのは、私にとってすごく大きな価値になりました。環境のバロメーターである流氷を何とかしたいという思いとも一致し、網走で工房を開く動機付けになりました。

ベトナムのガラス工場

知恵子 昇が沖縄の工場で職人として生きていく道を選んだ経緯も、私はすごいなと思っています。商売人の家の生まれなので、ガラスの学校を出たとしても、お客様が買ってくれる良い製品を作らないと工房としてやっていけないと算盤を弾いていました。ちょうど当時、インターネットで情報を検索できるようになったころだったので、多くの職人さんがいて技術を学べる工房を探したら、沖縄の工場とフィンランドのイッタラが浮上したそうです。

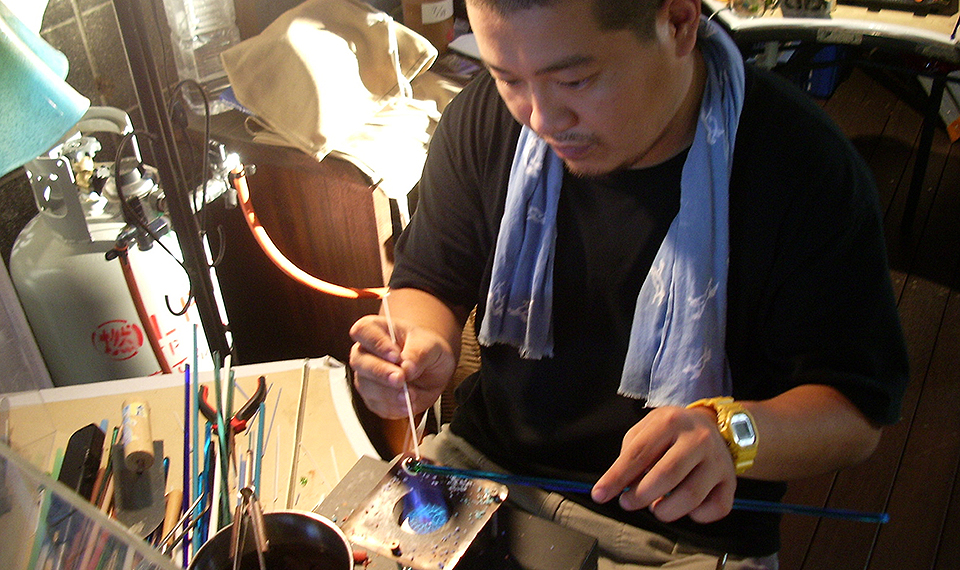

沖縄時代の軍司昇

沖縄の糸満市の工場は最初は掛け合ってもらえず、それでも糸満市と網走市が友好都市だったことから、何とかつながりを作ろうと市役所を通して掛け合ってもらって。県外からは人を入れないからと断られましたが、それでも押しかけて工場長に「ガラスを巻いてみろ」と言われ、やって見せたら「まあいいだろう」と入れてもらえることになりました。そして厳しくてもここで技術を手に入れて帰ろうと6年間頑張ったんですね。小さな個人工房に行っていたらできなかったと思います。 ちなみに、フィンランド大使館に行き、イッタラのヌータヤルヴィ工場にはメールを出したそうですが、返事は来なかったそうです。

昇 拙い英語で自分なりに書いたから、通じなかったのかもしれません(笑)。

リサイクルと環境教育ならサポートできる

―知恵子さんは、いつから環境問題に関心を持ったのですか?

知恵子 小学校のころに「リサイクルの重要性、リサイクルをしないと世界はどうなるか」という話を聞いたり、新聞やニュースで知ったのが最初でしたね。「地球温暖化で島がなくなる、ゴミ処理場も満杯になる」と聞き、これはどうにかしないと大変だと思ったのが、環境問題に関心を持ったきっかけでした。地球規模の問題に対して、一人一人が行動することに意味があると思い、今もそうですができることを探して地道に行動しています。

昇 もともと正義感が強いから、みんながなあなあにすることでも、先のことを考えてちゃんと意見を言うタイプだよね。

知恵子 自分では正義感が強いとは思っていませんが、昇にはよくそう言われます。それで、社会環境問題を考えて社会の意識を変えるには教育が重要だと思い、学校の先生になりたいと思った時もありましたが、結局別の道に進みました。 そして、昇から流氷硝子館の理念ややりたいことを聞いた時、「これだ!」と思い網走に行く準備をはじめました。オープンからの10年を振り返ると、国内や海外のお客様、修学旅行の生徒さんなどに伝える活動を通して環境教育にも関われるし、リサイクルにも関われることに魅力を感じています。私自身は、ガラスに興味はないのですが、この分野でならサポートしていけるなと思っています。

昇と一緒に流氷硝子館をやっていくと決めた理由はもう一つ、網走の環境の良さです。最初に訪れたのはオープンした年の5月だったのですが、北海道の中でも見たことのない、キラキラした海と湖と川に魅了されました。晴れた日だったので、先端までくっきり見えた知床連山の山並みは、ヨーロッパで見たアルプス山脈よりも美しく見え、今でも鮮明に覚えています。

網走から望む流氷と知床連山

首都圏での百貨店では、反応が得られず苦心

―流氷硝子館をオープンした2010年当時は、周囲の反応はいかがでしたか。

昇 オープン当初2~3年は、首都圏の百貨店の催事に呼ばれる機会も割と多くありました。「北海道だと小樽のガラス?なぜ網走でガラス?」という質問が多かったです。 運命的に出会った廃蛍光灯のリサイクルガラスの処理場や、工房を構えた網走との距離などの説明をしても、そのころはまだ環境問題やリサイクルに対する世間一般の人の関心は薄く、思った反応は得られず、「リサイクルなのに値段は安くないの?」「素材が劣るのでは?」といった声も聞こえてきました。

オープンに向けて改装中の流氷硝子館

知恵子 最初は良いPRの機会になると思いました。製品も確かに売れたので出展して良かったと思っていました。ただ、催事ではわたしたが伝えたいことへの反応が得られず、まだ時期尚早だと感じました。そこで、網走の工房に来てくれるお客様に地道に伝えていこうと方向転換しました。そうすると、網走の景色を見て話を聞いて、共感してくれる方が多く、伝わっていると手応えを感じてきました。海外の方の反応も良かったですね。だから気持ちが折れなかった。ちょっと早かったんだね、と。

SDGsが追い風になり、徐々に注目されるように

知恵子 地道に活動しながら共感してくれる人が来るのを待とうと、SNSを使って工房の日々の出来事などを発信し続けていました。そうすると、企業からコラボの声が掛かるようになったんです。 その一つが、2015年から通信販売のフェリシモでやっていたアップサイクルの企画です。そこから東急ハンズ渋谷店·新宿店で期間限定で取り扱いしてもらったり、「社会的な目的を持って生活すること」をコンセプトにした渋谷のTRUNK(HOTEL)の客室のグラスに採用されたりと、広がりが生まれました。さらに、持続可能な循環型社会を目指す環境に配慮し、先進的な取り組みをしている株式会社アレフでは、「びっくりドンキー」の客席の照明器具に流氷硝子のペンダントライトを、2020年現在70店舗1,200個使ってもらっています。

私たちの理念に共感してくれるところで「使ってもらう·販売してもらう」スタイルが、拠点である網走の工房とバランスが取れてうまく回るようになりました。 ここ1~2年は、2015年の国連サミットで採択された「持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)」の影響もあり、メディアに取り上げていただき注目される機会も増えて、「やっと伝わるタイミングが来た」と思えるようになり、うれしく思っています。

川湯温泉ユノハナガラス

教育旅行をリサイクルに関心を持つきっかけに

昇 オープン4年目ころから、教育旅行や企業研修として利用してくれる件数が増えました。そこでガラス体験だけでなく、数十分時間をもらって、流氷硝子館の環境問題に対する取り組みとガラスに関する話をさせてもらっています。子どもたちの「うわー」「へー」という歓声と大人たちからの激励が、やりがいにつながりますね。ここの景色を一緒に見ながら、「網走の流氷をなくさないためにやっているんですよ」と話すとよりリアルに感じてもらえて、腑に落ちる印象に残るようです。 イトムカ鉱業所のガラスは流氷硝子以外に建材のグラスウールやセメントの骨材として再生されています。ホタテ貝の貝殻を使ったり、乾電池のリサイクル素材でガラスに着色することができると話すと、意外性があって盛り上がります。ガラス製品作りも体験してもらって、リサイクルに興味を持つきっかけになればと思います。

小学生の社会見学の様子

知恵子 来てくれた人たちに、一つでも「行ってよかった」と思える何かが残ればと思って日々対応しています。意識を変えるのはほんのちょっとした何かだと思います。教育旅行で来てくれた小学生なら情報が入ると柔軟に変わるのではと思います。家に帰ってから、ここで聞いた話を家族に伝えてくれるとうれしいですね。 また、ガラス職人を目指す人が最初に興味を持ったきっかけが、教育旅行という場合も多いんですよね。この中の1人でも、将来手仕事やものづくりに関わってくれるといいなと願っています。

地元の高校の商業科の生徒にも、商品開発と販売の実習の授業に流氷硝子館で関わらせてもらっていて、生徒のアイディアを流氷硝子館で形にして、生徒自らがイベントで販売しているんです。企画~販売という流れをやってみるという体験を通して、難しさや達成する喜びを感じて、果敢にチャレンジする人になってくれたらと思っています。

今ここで、自分たちにできることを少しずつ

―ようやく時代が追いついてきたという感じですが、今後の展望はいかがですか。

知恵子 究極は、ガラス工房はやめていいと思っています。地球環境のことを考えると、エネルギーを使うガラス製作はやらないほうがいいのではと思いませんか? でも、ガラスは、何度でも溶かして繰り返しリサイクルできる優秀な素材なんですよ。 蛍光灯もいずれなくなると思いますから、そうなる前に流氷硝子の製品の回収をPRし、回収して何度でもリサイクルしやすい製品づくりを考えていきます。「使わなくなったけれど、これがあるから新しい器は買えない」と思っている方に、気兼ねなく流氷硝子を再利用してもらいたいですね。 それもいずれ需要がなくなれば、ガラスではないものに目を向けていければいいと思います。

昇 わたしたちは、輸入原料に頼ったガラス製品と環境に配慮したリサイクルガラス製品のどちらを選ぶか、使う人が選択できる状況が必要だと考え、提案しています。

やっぱりモノは作りたいですね。材料は世界中から集められますが、地域に限定して絞っていく方が楽しいですね。モノの見え方や人との関わりがよりリアルになりますから。廃棄物の中から使われないもの、みんなが注目しないものを見つけるのが面白いと思います。

様々な地域資源とリサイクル資源

知恵子 これからここでできる取り組みについての考えが、昇の意見と一致しました。 日本の電気の使用量は、冷暖房が多くを占め、夏のピークは7月8月、冬のピークは1月2月です。ガラスを溶かす溶解炉(窯)は、約1200℃前後で24時間動いています。 寒い時は窯の熱を暖房にリサイクルできていますが、暑い時に発する窯の熱は、室温を上げて、体に負担がかかるだけで再利用できていません。 そこで、今年から7月と8月に窯を動かさないようにしたい、熱を発しないことを目標に動いています。再生エネルギーへシフトするために、電力会社の変更も予定しています。

昇 近隣の町とも協力して、地域資源をもっとガラスに活用していきたいです。これまでも、川湯温泉の湯の花を使った琥珀色のガラスと、冷泉の堆積物を使った青緑色のガラスを、弟子屈町と流氷硝子館で開発を進めています。乾電池のマンガンで着色した「バッテリーブラウン」も、イトムカ鉱業所から「乾電池も何かに使えない?」と持ち掛けられたのがきっかけでした。「廃棄物を使ってこんな色ができるんだ」と面白がってくれる仲間が増えたらうれしく思います。また、なかなか実現できないのが、梱包材の脱プラスチックです。ガラス製品は持ち帰りや発送の際、割れないようにどうしても緩衝材が必要なので、環境にやさしい代替品を探しています。まだまだ見直しできることはありますね。

知恵子 これからも環境のことを考えてできることに取り組んでいきますが、ちょっと無理してでもできそうなことを見つけて、継続してみんなで取り組んでいきたいですね。

昇 ここ数年で、環境問題に関心を持つ人も増えましたし、そういった世界中の人とSNSを通してつながる機会も増えました。そんな中で流氷硝子館の商品や考え方を知ってもらい、リサイクル環境に配慮した商品を選ぶなど行動するきっかけになってくれたらと思います。

From Abashiri to the World one step at a time

The History and Future of the Ryuhyo Glass Museum

In this interview, Noboru Gunji, the head of the studio, and Chieko Gunji, the general manager, talk about what inspired them to open the Ryuhyo Glass Museum and their thoughts on future initiatives. (Recorded on February 2021)

The book that started the journey with glassmaking

– Noboru, what made you interested in glass?

When I was a child, my parents ran a retail store that sold toys and children’s clothes, and I thought I was to take over the store in the future. However, when I was in my third year of college, my father told me that he was closing the store and that I would have to figure out my own path. Up until that point, I had not attended many classes at the university and had not done any job hunting. I had been too absorbed in my American football team so I was suddenly forced to think about my future. “What could I do?” When I seriously thought about it, what came to mind was a career in manufacturing. Ever since I was a child, I had relatives who were fishermen and flower farmers so I had a longing to work with something that was hands-on. I was also into primitive activities such as making knives by pounding and crushing nails. Around that time, my father recommended to me a book called “Cheval’s Ideal Palace.”

My father is an avid reader and every so often he would recommend a book that he found interesting or thought would be a good fit for me. This book is the true story of Cheval, a French letter carrier who tripped over a stone one day and started to collect stones he found on his way to deliver mail. He then spent more than thirty years building a palace inspired by some foreign building on a postcard that he saw in the mail. The story was so shocking to me that it became a turning point. I thought, “If one was to continue to make something for over thirty years, they would most certainly encounter such an interesting and one-of-a-kind experience like no other.” After that, I diligently researched the manufacturing business and visited pottery kilns. One day, I went to a glassmaking studio in Otaru and was completely fascinated by the sight of molten hot glass moving organically and being shaped by craftsmen while it hardened.

When I thought about my future, another thing that came to mind was the scenery of Abashiri, my beloved hometown. I felt that my dream to set up a studio and create things in Abashiri would come true through glass making. I also saw a link between the ice, snow and lake water and beautiful glass work. When I consulted with people at the Otaru studio, they recommended that I go to a glassmaking school to learn the techniques in-depth. That is when I decided to take a break from college and go to school in Tokyo.

Chieko: Noboru and I were classmates at the university, but everyone was talking about what he was doing instead of coming to class. He was a bit of a unique presence. I was also amused in his choice to go to glassmaking school because it was very unusual.

Feeling uncomfortable with glassmaking using large amounts of fuel

– At that glassmaking school, you became to feel this big contradiction, right?

Noboru: I enjoyed learning new technology at the beginning of my work and during the first year. However, after the second year, I felt contradicted and uncomfortable consuming large amounts of fuel to make beautiful glasswork. It was because I watched a young girl’s speech on the Internet. It shocked me and has changed my whole view of the world ever since. The video was a speech given by 12-year-old Severn Suzuki, born the same year as me. She addressed world leaders at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Environmental Summit) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

In response to issues such as the depletion of the ozone layer and the extinction of wild animals, she urged us to stop destroying things we do not know how to fix. She also questioned how it was that we, who had everything, could be so greedy after she mentioned that she met a homeless child in Brazil who told her, “If I were rich, I would give food, clothing, medicine, a place to live, kindness, and love to every homeless child.” And to the adults in charge of the world and be passed on to the next generation, she concluded with strong words, saying, “You always tell us that you love us. If this is true, please prove it through your actions.”

I had long felt that the drift ice I saw every year in Abashiri was decreasing, so I was slightly aware of global warming being a problem. And after watching Severn Suzuki’s speech, my awareness became a conviction. From that moment on, I could not continue creating because watching my friends joyfully create glasswork was extremely difficult.

From that point on, the road to resolving my feelings of this contradiction began, and it is where the current philosophy of the Ryuhyo Glass Museum was originated. First, I started studying kilns to see if there was a way to reduce fuel consumption. I read engineering books on my own, went to workshops that were particular to making kilns and kept learning on how kilns worked. I also read books recommended to me. Instead of going to school, I visited workshops. I even bought a kerosene fan heater, dismantled it and made a burner for melting glass. At the vocational school, we had a year-end graduation project. Instead of creating any glass work, I made a model of a thermally efficient melting furnace along with a panel presentation to go along with it. The teacher insisted until the end that I present glass work; however, I pushed my idea through and made it my graduation project. Although I didn’t get a good evaluation from the school, the artists who visited were interested in my project. The people who actually ran workshops had the same feeling of contradiction all along. Until then, they thought it was a giveaway in making glass so they were actually interested in my proposal for a well efficient melting furnace. I was then convinced that pursing this issue was necessary, and I decided to continue my journey to resolve this contradiction.

Chieko: Noboru met key people everywhere he went, as he did when he got connected to his vocational school from the glass studio in Otaru.

Noboru: That’s right. The two years I spent at the vocational school were a particularly peculiar period. With my unresolved feeling looming on me, I would ask my teachers about the efficiency of kilns. But they would not tell me because it was not their specialty. But one of my teachers told me about a studio that specialized in kiln fuel efficiency so I decided to make a visit. At that workshop, they introduced me to specialized publications so I started to spend a lot of time in bookstores. There I was reading books on fluid mechanics and combustion engineering and wondered if I could use them in a glassmaking kiln. I was lucky in the sense to have great connections with a lot of people and a lot of information and at the perfect timing which made my purpose take form.

Encountering locally produced recycled glass

Noboru: After graduation, I decided to further study raw materials. I found a job at a large Ryukyu Glass factory in Okinawa. Ryukyu Glass was first made by recycling cola bottles discharged by the US military bases in Okinawa. Recycled glass bottles leave fine bubbles, which is usually not favored as an industrial product; however, Ryukyu Glass makes good use of these bubbles in its design which was something I learned a lot from. Okinawans who are not familiar with snow, expressed these bubbles as forms from the ocean, such as tidal waves. But as a native of Hokkaido, I thought, “This is snow! This is ice!” When it came time to open my own workshop, I already had a stock of ideas to express the bubbles as snow or ice.

In the meantime, I continued my research on recycled glass. Some workshops use recycled window panes and empty bottles. I heard that the composition of empty bottles varies depending on the manufacturer which results in an excessive amount of work to remove the labels as well as to actually collect and sort the bottles. And since bottles have a high melting point, they also use a considerable amount of fuel. On the other hand, I found out that the materials of fluorescent bulbs were homogeneous and had a low melting point, similar to the composition of blown glass. Thinking that there must be somewhere in the country where fluorescent lamps could be processed, I asked my father to help me in the search. Through various contacts, he found Nomura Kohsan Co., Ltd.’s Itomuka Plant located in Rubeshibe-cho, Kitami City, which is a neighboring town of Abashiri. I immediately negotiated with them and was able to receive a supply of raw materials. A year later, I left the factory in Okinawa and decided to open the Ryuhyo Glass Museum in Abashiri.

When I was working at the factory in Okinawa, I had the opportunity to teach glassmaking for three months at one of the directly managed factories based in Vietnam. At that time in Vietnam, there was a lot of energy among young people striving to aim higher. The Vietnamese are typically dexterous because they live on manual labor in the absence of goods. They also are extremely eager in earning a higher wage and to be able to live a better life which makes them quick learners. It was a culture shock for me because I had been taught that the Japanese were the dexterous ones. I asked myself, “While the Vietnamese people already have the technology to make such beautiful things, does it make any sense for us to continue doing so also in Japan?” So, the fact that I could actually make environmentally friendly glass using locally supplied raw materials was a big convincing point for me to move forward. It also was in line with my concern to do something about the drift ice which to me is one of the barometers of the environment. So that in all was my motivation for me to open a studio in Abashiri.

Chieko: I think it’s amazing how Noboru chose his destiny to live as a craftsman while he was at the factory in Okinawa. He was born in a merchant’s house. So, he knew even if he graduated from glassmaking school that if he wasn’t able to produce quality products that customers wanted, he wouldn’t be able to survive. At the time when it became possible to search for information on the Internet, he searched for a workshop where there were many craftsmen and where he could learn their techniques. He then found the factory in Okinawa and Iittala in Finland.

At first, the factory in Itoman City, Okinawa didn’t want to deal with him. But since Itoman and Abashiri were friendship cities, he tried to establish a connection with them through their city hall. They refused to let him in because they didn’t allow people from outside of the prefecture. But he persisted and the plant manager told him to show his skills at winding glass. The plant manager gave in and said, “Well, ok. That’s fine enough.” He worked hard for six years to acquire the skills needed there even though the job was tough. I don’t think he could have acquired the same experience if he had gone to a small private workshop. By the way, he went to the Finnish Embassy and sent an email to the Iittala Nuutajärvi factory, but he never got a reply.

Noboru: Maybe I didn’t get through to them because of my poor English skills (lol).

The ability to support recycling and environmental education

– Chieko, when did you first become interested in environmental issues?

Chieko: When I was in elementary school, I first heard about the importance of recycling and what would happen to the world if we didn’t recycle. I also learned about it from newspapers and the general news. When I heard that global warming would lead to the disappearance of islands and about the overflowing landfills, I knew that something had to be done. That’s when I became interested in environmental issues. I believe it is meaningful for each and every one of us to take action on this global issue. And as I do so now, I am consistently in search for actions that I can take.

Noboru: I have always had a strong sense of justice. So even if everyone might let go of certain things, I was the type of person that would consider the consequences and would always be vocal about it.

Chieko: I don’t consider myself to have a strong sense of justice, but Noboru often says that I do. There was a time I wanted to become a school teacher because I thought that education was important when it came to socio-environmental issues and to be able to change society’s mindset; however, I chose a different path. Then, when Noboru told me his philosophy of the Ryuhyo Glass Museum and what he wanted to do, I thought to myself, “This is it!” So, I started preparing my move to Abashiri. Looking back on the past 10 years since the museum opened, I am fascinated by the fact that I am able to be involved in environmental education and recycling through activities with domestic and overseas visitors as well as students on school trips. I myself am not that interested in actual glassmaking, but I think I can keep supporting him with these issues. Another reason why I decided a life at the Ryuhyo Glass Museum with Noboru is the wonderful environment of Abashiri. The first time I visited Abashiri was in May of the year it opened. I was mesmerized by the sparkling sea, lakes and rivers, which I had never seen before despite being from Hokkaido. Since it was such a clear day, I could see the Shiretoko Mountains all the way to the tip. It was more beautiful than the Alps that I had seen before while in Europe. I remember that day vividly.

The struggles in getting feedback from department stores in the metropolitan area

– What was the reaction of the people around you when you opened the Ryuhyo Glass Museum in 2010?

Noboru: In the first two to three years of our business, we were often invited to participate in events at department stores in the Tokyo metropolitan area. I was often asked, “If you are making glass in Hokkaido, why not in Otaru? And why in Abashiri?” When I explained that I felt a strong sense of fate because of the proximity between my studio in Abashiri and the recycled fluorescent lamp processing plant, I didn’t get the response I was expecting. The general public was not interested in environmental issues and recycling at that time, so instead, I got responses such as “Why isn’t the price cheaper since the products are made from recycled materials?” and “Aren’t recycled materials inferior?”

Chieko: At first, we thought it would be a good PR opportunity to have exhibitions in big cities, and, indeed, our products certainly sold. However, we felt it was too early to get a satisfying response to our main philosophy while exhibiting. So, we changed course and decided instead to communicate directly to customers who came to our workshop in Abashiri. As we did so, we began to feel that our message was getting across because many of our visitors could experience first-hand the scenery of Abashiri and feel attuned to our story. The response from foreign visitors were also great. That is what kept me going, and so I was able to take the not-so-great experience in Tokyo with a grain of heart.

Gradually gaining notoriety with the boost of the SDGs movement

Chieko: I tried to be patient in waiting for people who would sympathize with our work. I steadily kept sending out information about the daily activities of our studio through social networking services. As I did so, I began to receive calls from companies who wanted to collaborate. One of them was the upcycling project that we have been working on for the mail order company Felissimo since 2015. From there, our work spread to Tokyu Hands’ Shibuya and Shinjuku stores where the products were sold for a limited time only. Also, our glass was used for the guest rooms at the TRUNK (HOTEL) in Shibuya where the concept of “Living with a Social Purpose” was adopted. Also, as of 2020, Alef Co., Ltd., an environmentally conscious and progressive company that aims to create a sustainable, recycling-oriented society, is using 1,200 drift glass pendant lights in seventy of their Bikkuri-Donkey restaurants.

Our business concept of intertwining “using products” as well as “selling products” has been well established at our Abashiri workshop. During the past year or two, due to the influence of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted at the UN Summit in 2015, we have had more and more opportunities to be featured in the media and being able to attract attention. I am happy to think that time has finally come for our message to be conveyed.

Using educational trips as an opportunity to promote interest in recycling

Noboru: Since the fourth year of the museum’s opening, the number of visitors who use the museum for educational tours and corporate training has increased. In addition to the glassmaking experience, I also have a good chunk of time to talk about the museum’s environmental activities and facts about glass. The oohs and aahs from the children and the encouragement from the adults are very rewarding. When I tell them, “We are doing this to keep the drift ice in Abashiri alive,” they seem to grasp the urgent reality with a lasting impression. The glass from the Itomuka Plant is not only used as drift ice glass, but is also recycled as glass wool for building materials and as aggregate for cement. When I tell them that scallop shells or old batteries can be recycled and be used to color glass, they get excited since it is unexpected. I hope through our glassmaking experience they will also become interested in recycling.

Chieko: I deal with people every day, hoping to leave them with something that will make them feel like it was worth their trip. I think it only takes a little something to change people’s minds. I believe that elementary school students who come here on educational trips would adopt their newly received information and be able to easily make changes. It would be wonderful if they could go home and tell their families about what they learned here. Also, there are many cases where an educational trip became one’s aspiration in becoming glass craftsmen. It would be great if even one of our visitors would be involved in handicrafts and manufacturing in the future.

Students from the local commerce high school are also allowed to participate in classes on product development and sales at the Ryuhyo Glass Museum. I hope that the experience of planning and selling their ideas will make the students feel a joy of accomplishment through the difficulties and then in turn will become people who boldly challenge themselves.

Here and now, doing what we can, little by little

– It seems like the times are finally catching up with you, but what are your future plans?

Chieko: On the extreme end of the spectrum, I think we could just shut down our workshop entirely. Considering the global environment, don’t you think it would be better not to engage in such an energy-intensive glass production? However, glass is an excellent material that can be melted down and recycled over and over again. Eventually, I think that fluorescent lamps will be a thing of the past. So, before that happens, we want to promote the idea that our own glass products could be collected to be recycled once it becomes not of any use to the customers. I would like people who think, “I don’t use it anymore. But I can’t buy a new one because I just cannot get rid of it,” to recycle our glass products without hesitation. I hope that people will feel free to recycle our glass products. And when the demand for even that disappears, we should turn our attention to something other than glass.

Noboru: We believe that it is necessary that there exists an environment where consumers can choose between glass products made from imported materials and glass products made from environmentally friendly recycled materials. We are providing such a place according to that proposition.

I do want to continue to make things. Materials can be collected from all over the world, but it is more interesting to focus on locally acquired materials. It creates a more tangible and realistic connection with one’s surroundings and relationships. I think it is inspiring to find things in unwanted waste that people usually do not pay attention to.

Chieko: My own thoughts on initiatives we should take from here and now on were in alignment with that of Noboru’s. Most of the electricity used in Japan is for heating and cooling, with the summer peaking in July and August and the winter peaking in January and February. The melting furnaces (kilns) that melt the glass run twenty-four hours a day at around 1,200 degrees Celsius. When it’s cold, the heat from the kiln can be recycled for heating; however, when in hot weather, the heat from the kiln is not being reused and only raises the room temperature which also puts a strain on ourselves. So, this year, we are working towards our goal of not running the kiln in July and August as to not emit any heat. We are also planning to change our power company and shift to renewable energy.

Noboru: We would like to cooperate with neighboring towns to make more use of local resources for our glassmaking. So far, Teshikaga-cho and the Ryuhyo Glass Museum have been developing amber glass using mineral deposits from the hot spring, Kawayu Onsen, and jasper green colored glass using sediment from the local cold springs. “Battery Brown” which is coloring derived from the manganese of batteries, was invented by the Itomuka Plant when they were confronted with the enquiry of being able to reuse batteries. It would be awesome if there were a lot more people who would be amused by the fact that such colors can be created using waste.

Another thing that is difficult to achieve is the removal of plastic from packaging materials. Glass products need cushioning material to prevent them from breaking when taken home or being shipped so we are looking for environmentally friendly alternatives. There are still many things we need to work on.

Chieko: We will continue to work on what we can do to help the environment, but we would like to push for more and continue working together even if it is a little overwhelming.

Noboru: In the past few years, more and more people have become interested in environmental issues, and there are more opportunities to connect with people around the world through social networking services. I hope that people will be inspired by the products and ideas of the Ryuhyo Glass Museum and to take action such as choosing products that are recycled and environmentally friendly.

工房長 軍司 昇(gunji noboru)

1979年(昭和54年)12月 北海道網走市生まれ

1998年(平成10年)3月 北海道網走南ヶ丘高等学校卒業

1998年(平成10年)4月 北海道工業大学工学部経営工学科入学(現北海道科学大学)同アメリカンフットボール部入部※妻 知恵子と知り合う

2002年(平成14年)3月 北海道工業大学工学部経営工学科中退。ガラス工芸の道へ。同アメリカンフットボール部卒業

2002年(平成14年)4月~2004年(平成16年)3月 東京国際ガラス学院に入学し、ガラス造形の基礎を学ぶ。

2004年(平成16年)4月~2009年(平成21年)7月沖縄県糸満市琉球ガラス村に入社。ベトナム自社工場での勤務(3ヶ月間)

2010年(平成22年)5月 流氷硝子館 ガラス工房 工房長

2013年(平成25年)7月~食とクラフトのバザール「オホーツクまるごと市」を開催 実行委員長を務める2014年(平成26年)、2015年(平成27年)と開催後に東京農業大学オホーツクキャンパスの学生主体の「農大マルシェ」へイベント移行。オブザーバーとして現在も開催に関わっている。

2018年(平成30年)4月~オホーツク農山漁村活用体験型ツーリズム推進協議会 会長に就任。コネクトリップ カヤックガイドとしてサポート

好きなこと:スケボー、サーフィン、カヤック、野営

統括マネージャー 軍司 知恵子(gunji chieko)

1979年(昭和54年)12月 北海道稚内市生まれ

1998年(平成10年)3月北海道稚内高等学校卒業

1998年(平成10年)4月 北海道工業大学工学部建築工学科入学(現北海道科学大学)

2002年(平成14年)3月北海道工業大学工学部建築工学科 卒業。

2002年(平成14年)4月~2010年12月(平成22年)北海道内で建築関連の仕事に就く。

2011年(平成23年)1月~ 流氷硝子館 勤務

好きなこと:工程管理、海、ゴミ拾い、献血、逆立ち

インタビュアー 細川 美香

合同会社ハーヴェスト代表、フリーライター。

流氷硝子館ほか企業・官公庁等のウェブサイトおよびパンフレット、広報誌等のコピーライティング、雑誌・ウェブ媒体の記事制作を手掛ける。